-

13

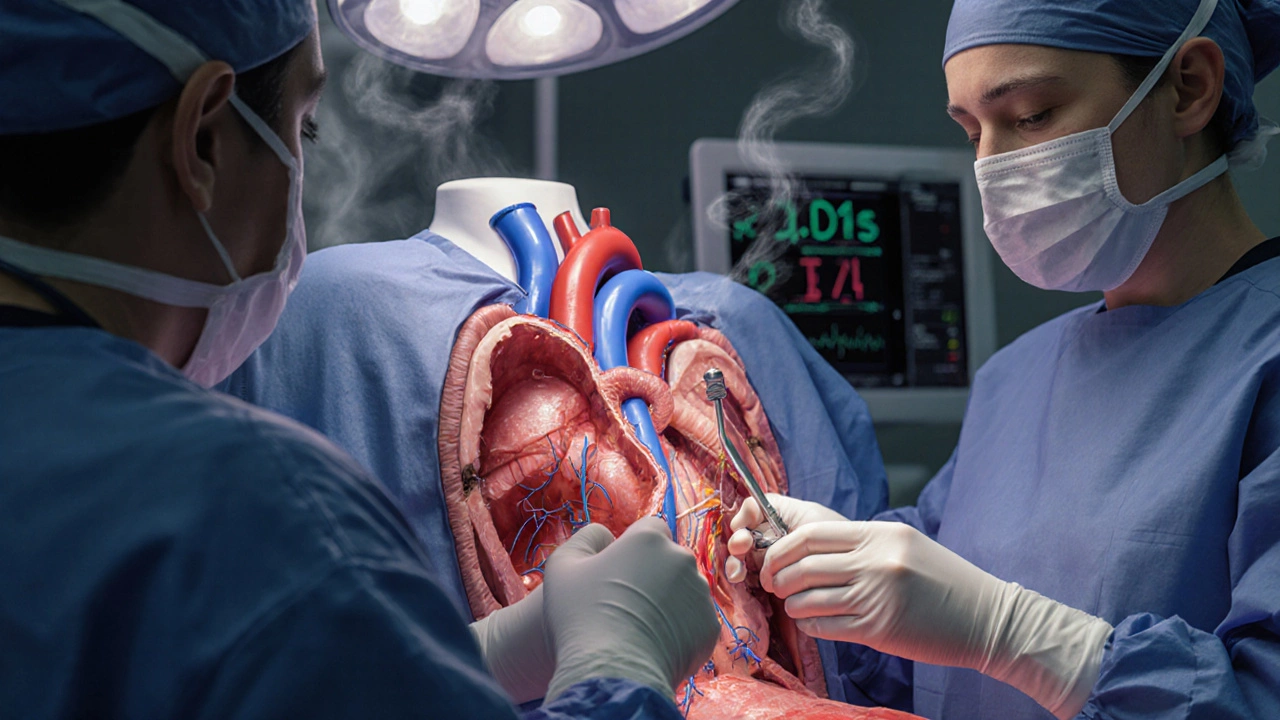

Is Open-Heart Surgery Very Serious? Risks, Recovery & What to Expect

Key Takeaways

- Open-heart surgery is a major operation, but modern techniques keep mortality around 1-3% for most procedures.

- Major risks include infection, bleeding, stroke, and heart rhythm problems; most are manageable with early detection.

- Pre‑operative testing (e.g., echo, stress test, labs) helps identify patients who can tolerate the operation.

- Typical hospital stay is 5-7 days, followed by 4-6 weeks of limited activity before resuming normal exercise.

- Less invasive alternatives (off‑pump CABG, robotic valve repair) may reduce recovery time but aren’t suitable for every case.

What "Open‑Heart Surgery" Actually Means

When doctors say open-heart surgery is a procedure that requires stopping the heart and using a heart‑lung machine (cardiopulmonary bypass) to keep blood circulating, they’re talking about the most invasive type of cardiac operation. Common examples are coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and valve replacement or repair.

How Serious Is the Procedure? Mortality & Major Complications

The word "serious" can feel vague, so let’s look at the numbers. Recent data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (2024) shows an overall open-heart surgery risk of 1.5% mortality for isolated CABG and about 2.5% for combined valve and bypass cases. These rates have dropped dramatically over the past two decades thanks to better anesthesia, refined bypass techniques, and stricter infection control.

Beyond death, the most frequent complications are:

- Bleeding - occurs in 2-4% of patients; usually controlled with re‑exploration or blood products.

- Infection, especially sternal wound infection, affecting roughly 1% of cases.

- Stroke - risk around 0.5-1%, higher in patients with atherosclerotic disease.

- Arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation, seen in 20-30% of patients, typically manageable with medication.

- Kidney injury - temporary rise in creatinine in 5-10% of cases, usually resolves.

Most of these issues are caught early because patients stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) for 24-48hours after the operation.

Pre‑Operative Evaluation: Reducing the Risks

Before the surgeon makes the first incision, a team of specialists runs a battery of tests to gauge whether you can handle the stress of stopping the heart.

- Cardiac imaging: A transthoracic echocardiogram (ECHO) visualizes valve function and wall motion; a cardiac CT or MRI may be ordered for detailed anatomy.

- Stress testing: Exercise or pharmacologic stress tests reveal how well your heart pumps under load.

- Blood work: CBC, coagulation profile, kidney and liver panels ensure you’re not at heightened bleeding or toxic risk.

- Pulmonary assessment: Spirometry checks lung capacity; poor lung function increases post‑operative ventilator time.

- Risk scoring: Scores such as EuroSCORE II or STS risk calculator combine age, ejection fraction, comorbidities, and surgical urgency to give a numeric mortality estimate.

If any red flags appear, doctors may adjust the operative plan, prescribe pre‑hab (exercise training), or suggest a less invasive technique.

During Surgery: What Happens Inside the Chest?

Once you’re under general anesthesia, a cardiopulmonary bypass machine takes over the work of the heart and lungs. The surgeon opens the sternum, places a cannula in the aorta and right atrium, and diverts blood through the machine, which oxygenates and pumps it back.

While the heart is still, the surgeon repairs or bypasses the blocked arteries, replaces faulty valves, or corrects structural defects. Modern perfusionists monitor temperature, flow, and blood gases continuously to keep the body stable.

When the repair is complete, the heart is rewarmed, the cannulas are removed, and the heart is shocked (defibrillated) to restart beating. The sternum is wired shut, and the chest is closed.

Post‑Operative Recovery: From ICU to Home

The first 24hours are spent in the ICU, where nurses watch your heart rhythm, blood pressure, and drainage from the chest tubes. Most patients are extubated (breathing on their own) within 6-12hours.

Key milestones:

- Day 2-3: Chest tubes removed, walking with assistance, pain control transitioned to oral meds.

- Day 4-5: Transfer to a regular floor, discharge planning begins.

- Discharge: Usually on day 5-7, provided wound healing is good and no arrhythmias are present.

After you leave the hospital, a structured cardiac rehab program lasts 6-12 weeks. The first month focuses on gentle walking, breathing exercises, and wound care. By week 6 you may start light resistance training, and by week 12 most patients can resume normal daily activities.

Less Invasive Alternatives: When They Make Sense

Not every patient needs a full sternotomy. Two popular alternatives are:

- Off‑pump CABG (also called “beating‑heart” surgery) - the heart continues to beat while vessels are grafted, eliminating the need for a bypass machine.

- Robotic or minimally invasive valve repair - small incisions between the ribs, camera‑assisted tools, and shorter hospital stays.

These approaches can reduce bleeding, infection, and ICU time, but they require specialized expertise and are best suited for patients with limited disease.

Checklist Before You Say Yes to Surgery

- Confirm the surgeon’s experience (≥200 open‑heart cases per year is a good benchmark).

- Ask for detailed mortality and complication stats specific to your procedure.

- Ensure pre‑operative testing is complete and any high‑risk findings are addressed.

- Discuss pain‑management plan and options for minimizing opioid use.

- Verify that cardiac rehabilitation services are available near your home.

- Ask about alternatives and why the team recommends open‑heart surgery over less invasive methods.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long does open‑heart surgery usually last?

The operative time varies by procedure but typically ranges from 3 to 6hours, including the time needed to set up and wean off cardiopulmonary bypass.

What is the chance of surviving an elective open‑heart surgery?

For low‑risk patients undergoing isolated coronary bypass, mortality is about 1-2%. For combined procedures or emergency cases, the risk can rise to 3-5%.

Will I need to stay in the ICU after surgery?

Yes, a 24‑ to 48‑hour ICU stay is standard to monitor heart rhythm, blood pressure, and drainage from the chest tubes.

Can I drive after being discharged?

Most surgeons advise waiting at least 4 weeks before driving, especially if you’ve had a sternotomy or are still on pain medication.

What are the signs of a post‑operative infection?

Fever, increasing chest pain, redness or drainage from the incision, and a rapid heart rate are warning signs. Call your surgical team immediately if any appear.

Comparison: Open‑Heart Surgery vs. Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery

| Aspect | Open‑Heart Surgery | Minimally Invasive (Off‑pump/Robotic) |

|---|---|---|

| Incision | Full sternotomy (6-8inches) | Small intercostal incisions (1-3inches) |

| Cardiopulmonary Bypass | Required | Often avoided |

| Typical Hospital Stay | 5-7days | 3-4days |

| Mortality Rate | 1.5-3% | 0.8-2% |

| Recovery to Light Activity | 4-6weeks | 2-3weeks |

| Best For | Complex multi‑vessel disease, combined valve + bypass, large aneurysms | Isolated single‑vessel disease, select valve repairs, patients needing quicker return |

Choosing the right approach depends on your specific heart condition, overall health, and the surgeon’s expertise. Discuss the pros and cons openly with your cardiac team.